Child

- About

- Meet The Team

- Conditions

- Aortic Stenosis

- Atrial Septal Defect

- Coarctation of the Aorta

- Complete Atrioventricular Septal Defect

- Heart Murmur

- Interrupted Aortic Arch

- Normal Heart

- Partial Atrio-Ventricular Septal Defect

- Patent Ductus Arteriosus

- Pulmonary Atresia with Intact Ventricular Septum

- Pulmonary Atresia with Ventricular Septal Defect

- Pulmonary Stenosis

- Right Aortic Arch

- Small Ventricular Septal Defect (Muscular)

- Small Ventricular Septal Defect (Perimembraneous)

- Tetralogy of Fallot

- Transposition of the Great Arteries

- Ventricular Septal Defect (Large)

- Dental Practitioners: Dental care in children at risk of Infective Endocarditis

- Looking after your child’s oral health

- Coming for an echocardiogram

- Outpatient Appointments

- Preparing to Come into Hospital for Surgery

- On Admission to the Children's Ward

- Visiting

- Operation Day

- Children's Intensive Care

- Daily Routine on Intensive Care

- Managing your child's discomfort

- Going Home

- Children's Cardiac MRI Scan

- Cardiac Catheter

- Reveal Device

- Ablation Procedure

- Pacemakers

- INR and Warfarin

- Lifestyle and Exercise Advice

- School Advice

- Attachment

- Yorkshire Regional Genetic Service

- Advice & Support Groups

- Your Views

- Monitoring of Results

- Second Opinion

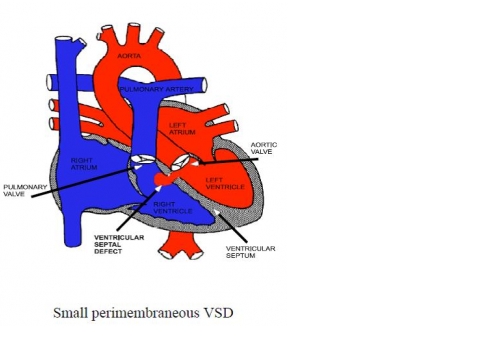

Small Ventricular Septal Defect (Perimembraneous)

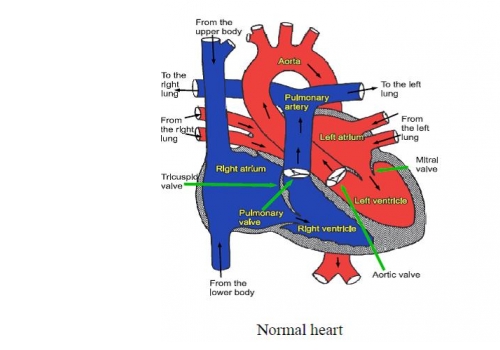

A ventricular septal defect is a hole in the wall between the two main pumping chambers of the heart (the ventricles). In the normal heart the left ventricle works at high pressure and pumps blood to the body and the right ventricle works at low pressure and pumps blood to the lungs. When there is a hole between the two ventricles (a VSD), blood flows from the left ventricle to the right ventricle through the hole. Some patients may have more than one VSD. When the hole occurs in the thinnest part of the septum it is called a “perimembraneous” VSD.

Most VSDs gradually get smaller or even close off completely on their own as the child grows. In some cases this happens within a few months, in others it may take many years and in some the VSD doesn‘t close at all. Even if a small VSD does not close by itself it does not usually need any treatment and does not usually stop the patient leading a completely normal life. Occasionally, as children with this type of VSD grow new abnormalities such as narrowing beneath the outlet valves of the heart or leaky valves can arise. Although such problems only occur in a very small number of children, they can be serious enough to need surgical treatment, so regular check ups in the outpatient clinic are recommended.

Tests

In most patients a test called an ultrasound scan of the heart (“echocardiogram”) is required to measure the size of the VSD and check whether the VSD is getting smaller as time goes by, or any new problems develop as the child grows.

General advice for the future

Patients with small VSDs can live normal active lives, including all kinds of sport. All patients with a VSD will be at risk of infection in the heart (called endocarditis). Such infections may be caused by infections of the teeth or gums. It is important to look after your child’s teeth and visit the dentist regularly (every 6-12 months). Ear or body piercing and tattooing are best avoided as they also carry a small risk of infection which may spread to the heart.