Child

- About

- Meet The Team

- Conditions

- Aortic Stenosis

- Atrial Septal Defect

- Coarctation of the Aorta

- Complete Atrioventricular Septal Defect

- Heart Murmur

- Interrupted Aortic Arch

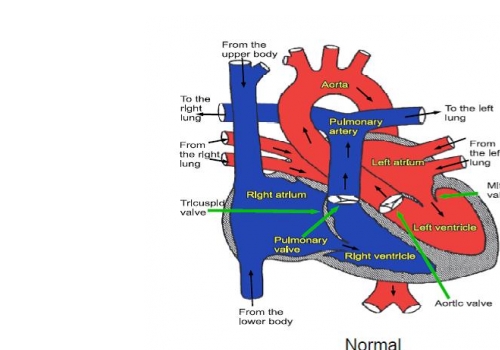

- Normal Heart

- Partial Atrio-Ventricular Septal Defect

- Patent Ductus Arteriosus

- Pulmonary Atresia with Intact Ventricular Septum

- Pulmonary Atresia with Ventricular Septal Defect

- Pulmonary Stenosis

- Right Aortic Arch

- Small Ventricular Septal Defect (Muscular)

- Small Ventricular Septal Defect (Perimembraneous)

- Tetralogy of Fallot

- Transposition of the Great Arteries

- Ventricular Septal Defect (Large)

- Dental Practitioners: Dental care in children at risk of Infective Endocarditis

- Looking after your child’s oral health

- Coming for an echocardiogram

- Outpatient Appointments

- Preparing to Come into Hospital for Surgery

- On Admission to the Children's Ward

- Visiting

- Operation Day

- Children's Intensive Care

- Daily Routine on Intensive Care

- Managing your child's discomfort

- Going Home

- Children's Cardiac MRI Scan

- Cardiac Catheter

- Reveal Device

- Ablation Procedure

- Pacemakers

- INR and Warfarin

- Lifestyle and Exercise Advice

- School Advice

- Attachment

- Yorkshire Regional Genetic Service

- Advice & Support Groups

- Your Views

- Monitoring of Results

- Second Opinion

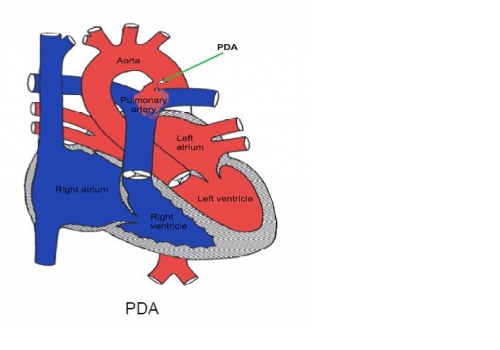

Patent Ductus Arteriosus

Click here for information on PDA In Newborn Infants.

The arterial duct (patent ductus arteriosus, or PDA) is a short blood vessel

connecting the two main arteries which come off the heart to feed the lungs and the body with blood. It is a normal part of the circulation before birth and normally closes by itself within the first week or so after birth. Sometimes the duct fails to close by itself. This results in the lungs becoming congested because they receive too much blood. This may cause only mild symptoms in young children (such as breathlessness) but if a duct is left untreated over a period of many years it may eventually lead to permanent damage to the heart and the lungs. This may prove fatal when the patient reaches later adult life, so it is important that large ducts are treated when the patient is young and before the heart or lungs have been permanently damaged. If the duct is small there is very rarely any risk of damage to the heart or lungs, but there is a risk of serious infection occurring inside the duct later in life. For that reason we recommend that even small ducts should be closed.

“Keyhole” treatment for PDA

Many ducts can be safely closed without opening the chest by placing a small plug made of metal mesh in the duct, inserted through a small tube (catheter) in the vein or artery at the top of the leg, using x-rays to guide it into position. The procedure is performed under general anaesthetic, the patient is usually in hospital for only one night and returns to full normal activities within a day or so after the procedure.

Once in the correct position inside the duct, the plug is unfolded by pushing it out of the catheter. It is held inside the duct by its specially designed shape and once in position it is released and stays inside the duct, permanently blocking it (although complete closure sometimes doesn’t always occur immediately after the device is implanted). The device stays inside the duct and becomes covered over by the patients own tissue during the healing process. A coil or plug will be visible on a chest x-ray for the rest of the patient’s life.

Risks of the keyhole procedure

Occasionally when we try to close the duct by keyhole treatment, the duct proves to be too big. If that happens surgery will be necessary, but it is not usually possible to arrange that immediately, so the patient is sent home and arrangements are made for the operation to be done later. Rarely, after the device in placed in the duct it may move out of position; when this happens with a coil it is not usually serious and it is usually possible to extract it and implant a larger device. If a plug moves out of position surgery may be necessary. There is also a risk of infection occurring on the coil or plug; this is very rare.

There is a small chance that the device will not quite completely close the duct; if there is only a very small duct left it can heal up on its own without treatment, but if it doesn’t we usually recommend a repeat procedure one or two years later. In a very small percentage of patients with a residual duct, the jet of blood past the metal device causes damage to the blood cells (this causes the urine to be very dark and the patient to become anaemic); in these cases it may be necessary to repeat the procedure to block the duct completely.

The risk to the patients’ life is extremely small.

Surgical treatment

Surgical treatment may still be required for some large ducts. This involves opening the side of the patient’s chest. Operations to close ducts are usually straightforward but require a hospital stay of a few days. There is a small risk even with surgery that the duct may not be completely closed, and in such cases the small residual duct can almost always be closed safely without further surgery, using keyhole treatment at a later date. There is always a very small risk with any kind of heart operation. The risk of dying at operation is extremely small (probably around one in a thousand), but complications such as fluid collecting around the lungs or the heart after surgery may sometimes occur. These are very rarely serious but can prolong the stay in hospital. Most patients are completely back to normal activities within 4 weeks after the operation.

The long term future

Almost all children will lead completely normal lives after the duct is closed, and no specific precautions or restrictions are necessary.